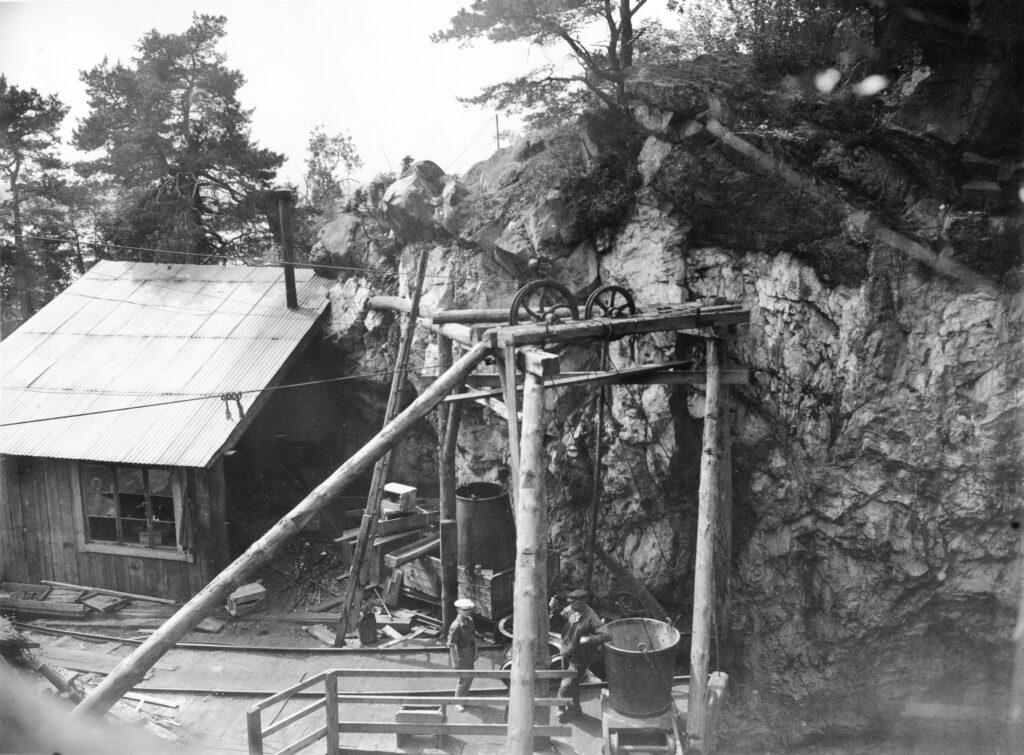

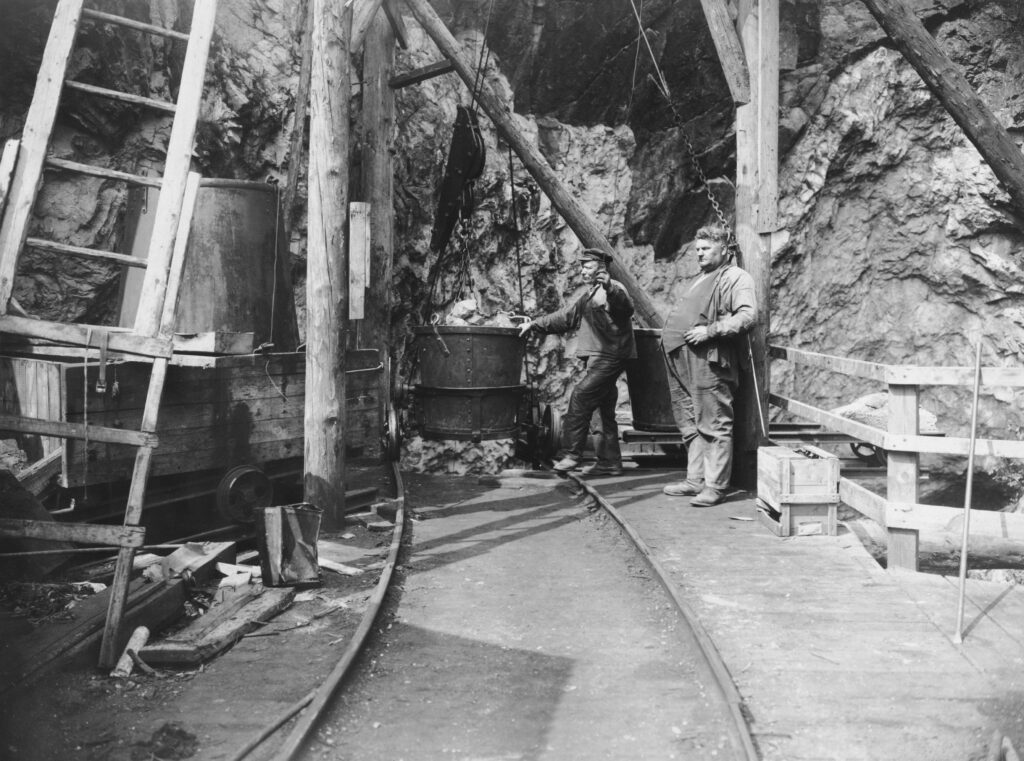

The mining took place using the simple methods of the time. In the beginning, cooking was used, where you set fire to the rock, which then became brittle. During the 19th century, gunpowder was used, and finally dynamite in the 1870s. As the demand for the minerals constantly increased, the open pit mine was supplemented in the 1860s with a deep shaft that came to reach 170m below the ground. The shaft inclined 60 degrees in a west-northwest direction.

Production reached its peak around the turn of the century in 1900, when Rörstrand had also started a successful production of technical porcelain for the emerging electrical industry, as well as sanitary porcelain. At the time, the mine employed a maximum of 47 islanders.

However, this was the beginning of the end for the mine. The feldspars began to appear, at the same time that Rörstrand’s porcelain factory had growing pains. The area around Karlberg Castle in Stockholm had become too crowded and the business was finally moved in 1926 to Gothenburg. Therefore, Rörstrand sold Ytterby mine, which was handed over to mine bailiff Carl Axel Jansson as pension insurance. This leased out the mining operation, the warp heaps were gone through one last time before the mine was finally closed down in 1933.

A new era began in 1953 when the mine was rebuilt to become a fuel storage facility for the Armed Forces. The old shaft was sealed with a 15m thick seal, and a 500m long tunnel was blasted to connect the shaft. You can read more about this under our pages about Ytterby Gruva and the Cold War.